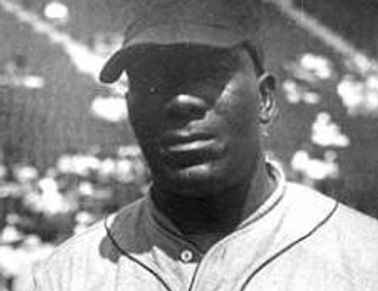

rube foster

September 17, 1879 – December 9, 1930

andrew rube foster

Andrew 'Rube' Foster is considered by baseball historians to have been the best African-American pitcher of the first decade of the 1900s. In addition to pitching, he founded and managed the Chicago American Giants, one of the era's most successful African-American baseball teams.

highlights

games managed

1,121

1905

-

1926

games managed

1,121

- Cuban X Giants (1905)

- Chicago Leland Giants (1907-1910, 1915)

- Chicago American Giants (1911-1914, 1916-1926)

- Louisville White Sox (1914)

1905

-

1926

career

Andrew "Rube" Foster was a professional baseball player, manager, and team executive working in the Negro Leagues and was elected to the Major League Baseball National Hall of Fame in 1981.

Rube Foster is considered by Negro League historians to have been perhaps the best African-American pitcher of the first decade of 1900s. Foster also founded and managed the Chicago American Giants, one of the most successful black baseball teams of the pre-integration era.

Most notably, he organized the Negro National League I.

The league became the first and longest lasting black professional sports league created for African-American ballplayers.

It operated as a professional league from 1920 until 1931, when it collapsed.

It was eventually replaced by the Negro National League II which operated from 1933 to 1945.

Foster carries with him the lasting legacy of notoriety that gained him respect as the "father of black baseball." [4]

Born in Calvert, Texas on September 17, 1879, his father was also named Andrew Foster, and was a reverend and elder community leader at his local African American Methodist Episcopal Church. [5]

Rube Foster started his professional baseball career in 1897 with the Waco Yellow Jackets, an independent black team, and that year he also saw playing time for the Hot Springs Arlingtons in 1901. [6]

Over the next year he gradually built up a reputation among white and black baseball fans of the and was scouted and signed as a pitcher by owner Frank Leland's Chicago Union Giants in 1902.

Leland's Union Giants at the time were the league's best team, and had accumulated some of the most talented players in all of professional black baseball.

Unable to shake it, Foster soon succumbed and adopted his longtime nickname, "Rube", making his official middle name later in his life.

In the early 1900s Foster was was released after a short hitting slump with a semi professional black baseball team, then signed with a white semi-professional team based in Otsego, Michigan, Bardeen's Otsego Independents.

According to Phil Dixon's American Baseball Chronicles: Great Teams, The 1905 Philadelphia Giants, Volume III:

In completing the summer of 1902 with Otsego's multi-ethnic team—the only multi-racial team with which he would ever regularly play for — Foster is reported to have pitched a total of twelve games.

Rube finished with a documented record of eight wins and four losses (8-4) along with 82 documented strikeouts.

Ironically, the strikeout totals for the other five games in which he appeared were not recorded.

If found, the totals would likely show that Foster struck out more than 100 for the Otsego club.

In the seven games where details currently exist, Rube Foster averaged around eleven strikeouts per game.

Toward the end of the 1902 season he joined the Cuban X-Giants of Philadelphia, who were at the time perhaps the best team in black baseball.

The season saw Foster firmly establish himself as an ace pitcher for the X-Giants' and cemented his legacy as a Negro League star.

In a postseason series for the eastern black championship, the X-Giants defeated Sol White's Philadelphia Giants five games to two (5-2), with Foster himself recording four games won as starting pitcher.

According to various accounts, including his own, Foster acquired the nickname "Rube" after defeating star Philadelphia Athletics left-hander Rube Waddell in a postseason exhibition game that took place sometime between 1902 and 1905. [7] [8] [9]

A newspaper story in the Trenton Times from July 26 of 1904, contains the earliest known example of Foster being referred to as "Rube," indicating that the supposed meeting with Waddell must have taken place earlier than that.

Recent research has uncovered a game played on August 2, 1903, in which Foster met and defeated Waddell while the latter was playing under an assumed name for a semi-professional team in New York. [10]

Now recognized across the Negro Leagues as an ace pitcher, Foster took his talent to the Philadelphia Giants for the 1904 season.

Legend has it that John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants, hired Foster to teach the young Christy Mathewson the "fadeaway", or screwball, though some historians have cast doubt on this story.

During the 1904 season, Foster won 20 games against all competition (including two no-hitters) and losing six games (20-6).

In a rematch with his former club, the Cuban X-Giants, he won two games and batted .400, leading the Philadelphia Giants to the black championship.

The following season in 1905, Foster — by his own account several years later — compiled an incredible record of 51–4 (though recent research has only been able to confirm a 25–3 record) and led the Giants to another series championship, over the Brooklyn Royal Giants.

The Philadelphia Telegraph wrote that "Foster has never been equalled in a pitcher's box."

The following year, the Philadelphia Giants helped form the International League of Independent Professional Ball Players, an association composed of both all-black and all-white teams in the Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware, area.

In 1907, Foster's manager Sol White published his Official Baseball Guide: History of Colored Baseball, with Foster contributing an article on "How to Pitch."

However, before the season began, he and several other stars (including, most importantly, the outfielder Pete Hill) left the Philadelphia Giants for the Chicago Leland Giants, with Foster named as player/manager.

Under his leadership, the Chicago Giants won 110 games (including 48 straight) losing only ten, before taking the 1908 Chicago City League pennant.

The following season the Leland Giants (now under the control of Rube Foster) tied a national championship series with the Philadelphia Giants, with each team winning three games.

Rube had suffered a broken leg in July of 1909, that proved to be a major set back for Foster - who rushed himself back into the lineup in time for an October exhibition series against the Chicago Cubs.

His pitching in the second game of the series, lead his team to a near victory, only to squandering a late inning three run lead, eventually losing the game a controversial play where a Cubs runner stole home while Foster was arguing with the home plate umpire.

The Leland Giants went on to lose the series, three games to nothing (3-0).

The Lelands also lost the unofficial western black championship that season to the St. Paul Colored Gophers.

Now in 1910, Foster began to use the power and influence he had acquired during his legal maneuvering to seize control of the team away from its founder, Frank Leland. [11]

He then proceeded to raid the league of some of its finest talent, assembling a team that he later recounted as his finest.

He began by signing ace John Henry Lloyd, stealing him away from the Philadelphia Giants; along with Pete Hill, Foster raided the Giants of second baseman Grant Johnson, catcher Bruce Petway, and pitchers Frank Wickware and Pat Dougherty.

The signing of John Henry Lloyd was a game changer for the Leleand's sparking a 123–6 record with Rube Foster contributing a 13–2 record as a pitcher/manager/owner.

The following season, Foster established a partnership with John Schorling, the son-in-law of Chicago White Sox owner, Charlie Comiskey.

The White Sox had just moved into Comiskey Park, and Schorling arranged for Foster's team to use the vacated South Side Park, at 39th and Wentworth.

Settling into their new home at Schorling's Park, the Leland Giants (now controlled by Foster) officially became the Chicago American Giants.

For the next four consecutive seasons, the Chicago American Giants claimed western black baseball's championship, losing only one title, a 1913 series against Lincoln Giants.

By 1915, the first serious rivalry in professional black baseball had emerged with C. I. Taylor's Indianapolis ABC's, who claimed the western title that season, defeating the Chicago American Giants in four straight games that July.

One of the wins ended in a forfeit when a brawl broke out between the two teams.

At the conclusion of the series both Rube Foster and C.I. Taylor began engaging the media openly in public dispute about the results of the game and the series..

In 1916, both teams again played for the western title.

This growing tension between the two men created a rivalry that contributed to a hunger for a more professional black baseball.

Declarations for more teams were made, but Foster, and Taylor, and the other major midwestern clubs were unable to come to official any agreement on the future of the league.

By this time, Foster was pitching very little, compiling only a 2–2 record in 1915.

His last recorded outing on the mound was in 1917; from this time on he would go on to manage only.

As a bench manager and team owner, Foster was a disciplinarian. He asserted control over every aspect of the game, and set a high standard for personal conduct for appearance, and professionalism amongst his players.

Given Schorling Park's huge and awkward dimensions, Foster developed a style of play that emphasized speed, bunting, place hitting, power pitching, and defense.

He was also considered a great teacher by many of his players, many of whom soon became managers themselves. This included Pete Hill, Bruce Petway, Bingo DeMoss, Dave Malarcher, Sam Crawford, Poindexter Williams, and others.

In 1919, Foster helped Tenny Blount finance a new ball club in Detroit, the Detriot Stars. He also transferred several of his veteran players to the team, including Hill, who was already suppose to manage a new team, and Petway.

He was giving investment into preparing for the formation of a more organized league.

That occurred the following year with the creation of the Negro National League I (NNLI).

In 1920, Foster, Taylor, and the other owners of the six other midwestern clubs met in the spring of that year to form a professional baseball circuit for African-American teams.

Foster, as president, controlled league operations, while maintaining ownership and management of the [Leland] Chicago American Giants.

Foster was a lightening rod for criticism. He was periodically accused of favoring his own team in league discussions, especially in matters of scheduling his Giants in the early years to have a disproportionate number of home games as well as league personnel.

Rube Foster seemed able to acquire whatever he needed from the other clubs with little resistance.

The Detroit Stars' best player in 1920, Jimmie Lyons was transferred to the Chicago American Giants for 1921, for Foster's own younger brother, Bill Foster, who joined the American Giants unwillingly with Rube forcing the Memphis Red Sox to give him up in 1926.

His critics were vocal in their belief that he had organized the league primarily for the purposes of booking games for his team, the Chicago American Giants.

However, with a stable schedule and reasonably solvent opponents, Foster was able to improve the overall gate receipts for the league significantly. It is also true that when opposing clubs lost money, he was known to help them meet payroll, sometimes out of his own pocket. [12]

His won the new league's first three pennants consecutively before being overtaken by the Kansas City Monarchs in 1923.

At that time the two most important franchises in the East were the Hilldale Ball Club and Bacharach Giants, and both teams pulled out of an agreement with the Negro National League (NNL) and founded their own league, the Eastern Colored League (ECL).

The ECL then raided the older circuits of the Negro Leagues for players they saw as under valued assets.

Foster's ace pitcher Dave Brown was among the player poached.

After several high profile incident =s of poaching the leagues reached an agreement to respect one another's contracts, and also to play a yearly World Series.

After two years of finishing behind the Kansas Monarchs, Rube had cleaned house in spring of 1925.

He released several of his veteran players including Lyons and pitchers Dick Whitworth and Tom Williams.

On May 26, Foster was nearly asphyxiated by a gas leak in Indianapolis.

Though he recovered and returned to his team, his behavior grew increasingly erratic moving forward.

Foster instituted a split-season schedule format, with his Chicago American Giants finishing third in both halves of the season. [13]

The 1926 season saw him complete his team's reshaping by leaving only a handful of veterans from the previous championship squads of the 1920’s off the team.

The club finished third in the season's first half, but Foster would never finish the second.

Over the years, "Foster grew increasingly paranoid. carrying a revolver with him everywhere he went."

He began suffering from delusions, including one where he believed he was about to receive a call to pinch hit in the World Series.

Sadly, Rube Foster was institutionalized midway through the 1926 season at an asylum in Kankakee, Illinois. [14] [15]

His Chicago American Giants and the Negro National League I lived on led by Dave Malarcher.

The Giants won the pennant and World Series in both 1926 and 1927—with the league clearly suffering in the absence of Foster's leadership.

Foster died in 1930, never recovering his sanity and a year later the league he had founded fell apart.

Foster is interred in Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois. Thousands attended his funeral in Bronzeville, Chicago, including "an overflow crowd of 3,000 people who 'stood in the snow and rain.' At his funeral, his coffin was closed, according to attendees, "at the usual hour a ballgame ends." [16]'

In 1981, Rube Foster was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He was the first representative of the Negro Leagues elected as a pioneer executive and player.

.

On December 30, 2009, the U.S. Postal Service announced that it planned to issue a pair of postage stamps in June honoring Negro leagues Baseball. [17]

On July 17, 2010, the Postal Service issued a se-tenant pair of 44-cent, first-class, U.S. commemorative postage stamps to honor the all-black professional baseball leagues that operated from 1920 to about 1960.

One of the stamps depicts Rube Foster, along with his name and the words "NEGRO LEAGUES BASEBALL". The stamps were formally issued at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, during the celebration of the museum's twentieth anniversary. [18]

The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum hosts the annual Andrew "Rube" Foster Lecture, in September. [4]

In 2021, Rube Foster was posthumously inducted into the Chicagoland Sports Hall of Fame. [19]

On November 10, 2021, the United States Mint announced the designs for the 2022 Negro Leagues Centennial Commemorative coins, with Foster featured on the $5 gold half eagle. [20]

players

Oscar Charelston

Oscar Charelston

Oscar Charelston

Oscar Charleston played and managed in the Negro Leagues as an outfielder, first baseman and pitcher. Charleston would later become manager of the Indianapolis Clowns.

Cool Papa Bell

Oscar Charelston

Oscar Charelston

Cool Papa Bell played centerfield in the Negro Leagues from 1922 to 1946. played for the powerhouse Kansas City. Monarchs, Pittsburgh Crawfords, and Homestead Grays.

Buck Leonard

Oscar Charelston

Buck Leonard, along side Josh Gibson formed the best three-four, hitting tandem in the History of the Negro Leagues, leading the Homestead Grays to dominance.

Satchel Paige

Satchel Paige began his 20 year career in the Negro Leagues pitching for the Chattanooga Lookouts. He would later make his MLB debut at age 42 for the Cleveland Indians.

Cumberland Posey

Cumberland Posey

Cum Posey was a veteran Negro Leagues team owner, player, and league executive. He is the founding member of two leagues, and a Hall of Fame Basketball player.

Jackie Robinson

Cumberland Posey

Jackie Robinson is the first African American to play Major League Baseball. He broke baseball's color barrier in 1945, by signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Roy Campanella

Roy Campanella

Roy Campanella

Roy Campanella played one season in the Negro Leagues, signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers just one season after Jackie Robinson’s debut in Major League Baseball.

Gus Greenlee

Roy Campanella

Roy Campanella

Gus Greenlee was a driving force behind the organization of the Negro National League I. During his time involved with Negro Leagues he owned several profitable side businesses.

Henry AAron

Roy Campanella

Candy Jim Taylor

Major League Baseball’s all-time leader in home runs with 755, few know Aaron began his baseball career in the Negro Leagues as a shortstop for the Indianapolis Clowns.

Candy Jim Taylor

Candy Jim Taylor

Candy Jim Taylor was a professional third baseman, manager, and brother of four professional playing Negro Leaguers. His career in baseball spanned over 40 years.

Cristóbal Torriente

Cristóbal Torriente, often called the Babe Ruth of Cuba, played as an outfielder in the Negro Leagues from 1912-1932. He was most known for his incredible power to all fields.

Rube Foster

Considered perhaps the best African-American pitcher of the first decade of the 1900s, Foster also founded and managed the Chicago American Giants.

Larry Doby

Larry Doby was the second African-American baseball player to break baseball's color barrier and the first black player to play in the American League.

Josh Gibson

Even at the catchers position, Josh Gibson's display of power in his famed Negro Leagues career is something rarely seen in the history of Major League Baseball.

Sol White

King Solomon "Sol" White played baseball professionally as an infielder, manager and league executive. White is considered to be one of the pioneers of the Negro Leagues.

Ben Taylor

Ben Taylor

Born in July 1888, Ben Taylor was the youngest of 4 professional Negro Leaguers, including Candy Jim Taylor, C.I. Taylor, and Johnny Steel Arm Taylor.

Biz Mackey

Ben Taylor

Biz Mackey

Biz Mackey was regarded as one of the Negro Leagues premier offensive and defensive catchers, playing across several leagues from late 1920s and early 1930s.

Nat Strong

Ben Taylor

Biz Mackey

Nathaniel Strong was a Negro Leagues sports executive, businessman, team owner and founding member of the Negro National League I,

Monte Irvin

Turkey Stearnes

Monte Irvin flourished as one of the early African-American players in MLB, making 2 World Series appearances for the New York Giants, playing along side Willie Mays.

Turkey Stearnes

Turkey Stearnes

Norman Turkey Stearnes played professionally in the Negro Leagues, and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2000.

Willie Mays

A can’t miss five-tool player, Mays began his professional baseball career with the Black Barons, spending the rest of his career playing MLB for the Giants and Mets.

Steel Arm Taylor

John Boyce Taylor was the second-oldest of 4 baseball-playing brothers, the others being Charles, Ben and James. For the 1899-1900 seasons, Taylor won 90% of his games starting pitcher for the Giants.

Buck O'Neil

Buck signed with the Memphis Red Sox for their first year of play in the newly formed Negro American League (NAL). His contract was sold to the Kansas Monarchs the following year.

negroleagues.org

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience.